How Many of Us Are Able to Forgive Without Collecting Our "Pound of Flesh?"1 Corinthians 6:12-20;

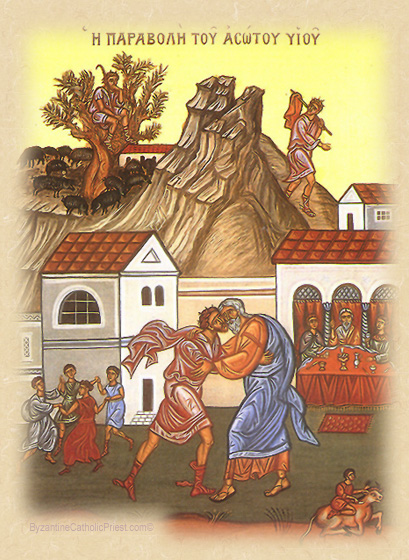

Luke 15:11-32. The Second Sunday of the Triodion, known as The Sunday of the Prodigal Son. The Translation of the Relics of Our Holy Father John Chrysostom.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

12:25 PM 1/27/2013 — Last Sunday the Triodion opened with the parable of the Publican and Pharisee, illustrating our need to acknowledge that we are sinners. The tag line, as I recall, was “The Doctor can't cure you if you don't tell him where it hurts; and Jesus can't forgive you if you don't tell him your sins.” To that we added words of the Blessed Apostle Peter: “Anyone who says he is not a sinner is a liar.”

This week, our Lord presents to us a story about forgiveness which is so familiar to us that we automatically assume we know what it means: the prodigal son returns and his father forgives him, illustrating the comforting fact God is ready to forgive us no matter how far we stray. That's a good third grade explanation of the parable, but it isn't sufficient because there are more than two characters in this story: there's a son who goes astray and a father who forgives him; but, there's also another son, and he's the one who's important.

Every once in a while, especially this time of year as Lent approaches, a priest will run into people in confession who've been away from the Church for a long time; and it's usually because something terrible happened to them, and they decided to blame God: they lost a spouse or a child or had to suffer some terrible illness; and this shook their faith in God as if, somehow, God let them down: "I lived a good life, so why would God let this happen to me?" Every once in a while, especially this time of year as Lent approaches, a priest will run into people in confession who've been away from the Church for a long time; and it's usually because something terrible happened to them, and they decided to blame God: they lost a spouse or a child or had to suffer some terrible illness; and this shook their faith in God as if, somehow, God let them down: "I lived a good life, so why would God let this happen to me?"

I always recommend them to read the book of Job; and many of you have heard me preach from it at funerals. It begins by saying how there was no man in all the world more pleasing to God than Job, and how God allowed Job to be tested by Satan by having everything taken from him, including his children, and finally being afflicted with a horrible chronic illness. And his wife thinks he's crazy because he continues to praise and worship God. And Job's response to her is one of the most electrifying verses in the Bible: "Naked I came forth from my mother's womb, naked I shall return. The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord."

Now, we don't see that kind of faith very often. Our faith is not unconditional like Job's. We put in the hours by living a good life, then we expect God to pay the wage—in spite of the fact that Jesus told us, on more than one occasion, that reward and punishment are not in this life, and that God allows it to “rain on the just and unjust alike.” But we ignore all of that. We still believe that God should reward us for our good life now; and, if he doesn't then there's something wrong with him.

And that's the real message of this parable. Yes, of course it is a story about forgiveness; and we should feel comforted by the fact that God is always willing to forgive as long as we are willing to repent. But there's a lot more to the story than that. We often overlook the fact that, in having the father in the story react the way he does to his elder son, Jesus has completely thrown out every notion of human justice there ever was.

We always overlook the older son in this story. We always focus on the younger son, the prodigal son; that’s why we call it “the Parable of the Prodigal Son.” But the older son is important, too. He goes to his father and makes two accusations: he accuses his brother of wasting his inheritance on loose women;—an accusation which we know to be false, since we know from the previous paragraphs that the younger son simply ran out of money—but, he also accuses his father of being unfair, and this accusation is quite true. In doing what he does for the prodigal son, the father is unfair; he has done a gross injustice to his other son.

And isn't the reaction of the older son exactly how we react to God when we think he's been unfair to us? We lose a loved one to death, for example—a child or a spouse or a parent—and we don't care that God has taken that person to himself; we only care what we think he's done to us. Or we or someone we love is forced to suffer a long or painful illness. We don't care that he's given that person a great opportunity to avoid Purgatory by allowing them to sacrifice here on earth; we only want him to be nice to us now.

In the bulletin this week I reproduced for you part of an old homily I found on the Vatican web site by an African bishop, Dominique Mamberti, who takes an even different approach to understanding this parable: he posits that the important person in the story is the father, and points out that there are many different ways the father could have forgiven the prodigal son upon his return, some of which seem very familiar to us. He could scold him. He could have offered his forgiveness conditionally, demanding restitution or, at the very least, an apology; and, is this not the way most of us tend to forgive others? We make ourselves feel better by saying, “I forgive you,” but we always make sure to collect our pound of flesh in the process. Our forgiveness is really nothing more than a kind of emotional blackmail: “I forgive you, so long as you continue to feel guilty about it.”

But, as Bishop Mamberti points out, the father in the parable doesn't do any of that; instead, he interrupts his son's apology and throws a party, pretending that the offense never took place. Couple that with my own reflections about the conduct of the elder son, and you've got a very different concept of Christian forgiveness than most of us would be inclined to accept, and which may help us to appreciate the nature of God's forgiveness to us when we've sinned.

As a society, we've become obsessed with the whole concept of fairness, and, as Americans, we've been conditioned to frown upon any hint of injustice; and, this kind of thinking infects our relationship with God. The use of this familiar parable as the Gospel lesson of today's Liturgy gives us an opportunity to reflect on the fact that God doesn't deal with any of us according to the rules of human justice. God owes us nothing. And even if we live a perfect life of perfect virtue, God owes us nothing. Living the way God wants us to live is what we owe to God; and, to quote a line I've used many times before, salvation—which is the only goal of the Christian’s life—is not payment for services rendered.

As the Triodion continues and we begin to move ourselves into a spirit of self-denial and self-evaluation in preparation for the Great Fast, let us pause to reflect on what kind of conditions we may have placed on our love and worship of God, and be thankful for the fact that God has placed no such conditions on us, making forgiveness of our sins only a confession away.

|