|

2:13 PM 1/2/2011 — It’s certainly not a new phenomenon that Christian holy days have to compete with secular holidays. In the pagan world of marketing and advertising, the Christmas season begins the day after Thanksgiving, and ends abruptly on Christmas Day. In the life of the Christian, the Christmas season begins on Christmas day, and the fifteen day celebration is marked by a variety of feasts commemorating numerous important events in the life of our Lord, culminating in his baptism in the Great Theophany.

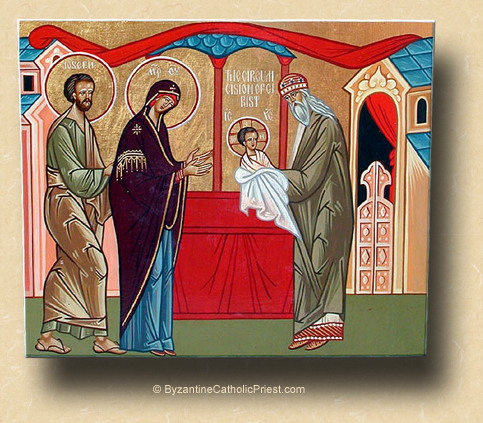

One of the most important of those commemorations suffers the indignity of falling each year on the first day of the calendar year. It falls on that day because of Jewish law: every male child is to be circumcised on his eighth day; and, in this particular case, perhaps the cause of remembering the circumcision of our Lord is destined to be lost forever, given the fact that the secular holiday with which it competes is the annual celebration which marks the greatest feat in the history of marketing: the distillation of alcoholic fluids from common grains at a cost of about 35˘ per gallon, and the successful marketing of them to the general public at a 2000% markup.

But the suggestion that the Christian feast be moved to another day would not only be a shameful surrender, but would also distort the whole point of the commemoration; for what’s important about yesterday’s feast is not simply remembering another event in the life of our Lord,—as if that alone isn’t important enough—but what this particular event signifies.  Think back to the Sunday before the Nativity—the Sunday of the Genealogy, as it’s called—and why I explained to you how important it was not to omit the readings of all those unpronounceable Old Testament names: Matthew’s Jewish audience will only know that Jesus is the Messiah if he fulfills all the requirements laid out by the holy prophets. The genealogy proves that. Yesterday’s feast proves the same, but in a way that looks forward rather than back. Think back to the Sunday before the Nativity—the Sunday of the Genealogy, as it’s called—and why I explained to you how important it was not to omit the readings of all those unpronounceable Old Testament names: Matthew’s Jewish audience will only know that Jesus is the Messiah if he fulfills all the requirements laid out by the holy prophets. The genealogy proves that. Yesterday’s feast proves the same, but in a way that looks forward rather than back.

Jesus himself, remember, said that he came not to abolish the law and the prophets, but to fulfill them. Jesus doesn’t cancel Judaism, he completes it. His parents take him to be circumcised on the eighth day after his birth because the Law of Moses commands it; and, as Jesus grows into manhood and commences his public ministry, we see him, again and again, doing everything according to the law: he went for the feasts to Jerusalem; he sent the people he had cured to the priests to perform the sin-offering commanded by Moses; he paid the temple tax every year; admonished the multitudes who came to hear him preach to obey the Scribes and Pharisees as those who sit in Moses’ place; and, even though it had been introduced long after Moses, he participated every Sabbath in the Synagogue service, fulfilling his duty to read and comment on the Word of God whenever it was his appointed turn to do so. On those few occasions where he appears at first to be violating the law, such as curing someone on the Sabbath, he is able to point out to the Pharisees criticizing him how they have misread the law; with all of his interpretations being confirmed by the Talmudic Tradition.

In every way, our Savior paid dutiful attention to the religious system under which he was born; and, even after he had left them in bodily form and ascended back into the heaven from which he came, and sent the Holy Spirit down upon them,—at which point one might argue that the Law of Moses would no longer apply—the Apostles continued to follow his example. No, they never did require adherence to the law—particularly the law of circumcision—as necessary for salvation; but neither did they forbid or criticize adherence to it. Even St. Paul, who was the first to champion the rights of the Gentile Christians not to be circumcised, insisted that all the laws should be followed so as not to cause scandal or offense; and himself circumcised Timothy when he chose him to be his assistant, so that he might be accepted by the Jews to whom he was being sent. All of this is clear in the New Testament.

Now, I did say that yesterday’s feast points more to the future than the past, and here’s how: we live in an age which prides itself on its devotion to authenticity: we want our politicians to be honest; we want our history to be critical; we want our news to be accurate; we want the things we buy to perform as advertised; and we want our religion to be relevant and address the needs of today. The problem is that the litmus test we often impose on religion is too similar to the litmus test we impose for everything else, when it should be the other way ‘round: it’s our religion that imposes the litmus test on our authenticity. It’s way too easy for us to look at everything our Church requires of us—by way of moral absolutes, by way of liturgical requirements, by way of interior conversion—and to judge them as good or bad—as applying to us or not applying to us—based on some twisted misinterpretation of conscience; when what should be happening is that the teaching of Christ, revealed in Holy Scripture, explained by the Fathers, expanded and made practical by the teaching of the Church, should be the litmus test by which we judge ourselves every day.

Now, it’s possible that we in the Eastern Church have something of an advantage in comprehending this, given that we have preserved an adherence to tradition in our Liturgical life that few Christian communities can replicate; but, if we can’t translate that into the very core of how we live our lives, then it’s nothing but an empty shell. The Gospel of Jesus Christ is not merely an historical record, nor is the liturgy of the Church a museum piece; nor is the life of a Christian a matter of saying “Merry Christmas” instead of “Happy Holidays,” or wearing some piece of Christian-inspired jewelry.

When his parents took him to be circumcised on the eighth day in conformity to the law, Jesus, as God, knew exactly what he was doing: he was setting not only the pattern for his own life on earth, not only the pattern for how his Apostles would establish the Church, but giving us our first lesson in Christian living. We do not conform the faith to suit us; we conform ourselves to suit Christ. And the next time someone challenges you, saying, “Why do you Byzantine Catholics do this, that or the other?” it isn’t at all an inadequate response to say, “Because it is required.”

Father Michael Venditti

|

Why do we do what we do? Because it is required!Explaining the Feast of the Circumcision. The Sunday after the Nativity. The Sunday before the Theophany.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |