When God Says, "No."

The First Friday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the secondary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Samuel 8: 4-7, 10 22.

• Psalm 89: 16-19.

• Mark 2: 1-12.

The First Friday after Epiphany.

Lessons from the dominica,* according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Romams 12: 1-5.

• Psalm 71: 18, 3.

• Luke 2: 42-52.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:22 AM 1/12/2018 — Today’s Gospel lesson is Saint Mark’s account of the paralytic lowered through the ceiling to be cured by our Blessed Lord. About a week before Christmas we had heard Saint Luke’s account of the same incident, the two being being almost word-for-word identical. Our Lord forgives the man’s sins first, as in all the Gospels physical suffering is an analogy for sin; but Mark today adds an interesting twist to his report of this event. There are, apparently, some Scribes hanging around who are incredulous at our Lord’s priestly absolution of the man’s sins, calling it a blasphemy, and—the way Mark tells it—our Lord seems to cure the poor fellow simply to prove them wrong. Of course, we don’t need to ask whether our Lord would have performed the cure if the Scribes had not been there, since, as I said, sin and illness are intertwined throughout the Gospels: the forgiveness of sins is the curing of a disease. Of course, as a former pastor for many years, my thoughts immediately go the question of who’s going to fix the hole in the roof, but neither Luke nor Mark choose to report on that.

But, being that this event in our Lord’s life is being repeated for us, maybe we should take a brief look at our first lesson from the First Book of Samuel. For Israel, this was the era of the Judges. The Prophet Samuel had led the military campaign that conquered the Canaanites so Israel could take possession of the land God has promised to Moses, and, in his old age, had appointed his sons as “judges” to carry on this legacy of spiritual leadership that had little to do with political power; but, as our first lesson opens, it seems there’s some discontent among the ranks. Israel is on the verge of becoming a nation in its own right, and has, for the first time, encountered other nations, conquering some of them. There’s a passing reference to some incompetence or even corruption on the part of Samuel’s sons, but reading between the lines, it’s clear there’s also a tinge of envy on the part of the people. They want to be like other nations, and all the other nations they’ve encountered are ruled by a king. Samuel is distressed at this because he regards it as a lack of faith; he tries to explain that God alone is their King and, if they’re faithful the covenant God made with Abraham, they should need no other.  He outlines for them all the evils that kings often suffer upon their people, but they are relentless in insisting that they need to be like everyone else. He asks God about it in prayer, and God agrees with him that this is a disturbing turn of events, but gives Samuel permission to anoint a king for Israel anyway, and this will lead to Samuel choosing and anointing Saul as the first King of Israel, thus inaugurating the long era of the Kings, which takes up nearly most of Old Testament history. He outlines for them all the evils that kings often suffer upon their people, but they are relentless in insisting that they need to be like everyone else. He asks God about it in prayer, and God agrees with him that this is a disturbing turn of events, but gives Samuel permission to anoint a king for Israel anyway, and this will lead to Samuel choosing and anointing Saul as the first King of Israel, thus inaugurating the long era of the Kings, which takes up nearly most of Old Testament history.

The reflection for us today is both the failure of the people to rely on their faith to overcome the envy they feel towards longer established nations—their desire to be part of the “international community,” to coin a modern phrase—but also the fact the God gives in and allows it. We have a saying, as you know: “Be careful what you ask for.” Remember that God created us with a free will. He does not force Himself upon us, we have to choose Him for ourselves. This dialog between God and His people, with Samuel serving as intermediary, is an analogy to our own relationship to God, both in prayer and in moral living, with Christ as intermediary. The moral of the story is that we can ask our Lord for whatever we want, and He may grant it to us, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s what He, in fact, wants for us. Remember what I mentioned a long time ago when telling you about my time with the Carthusians in Vermont. Saint Bruno prayed that God would never send him any kind of supernatural or mystical experience because he didn’t want to think that he needed it, and wrote in his rule that any monk who did receive such a thing was to keep it to himself.

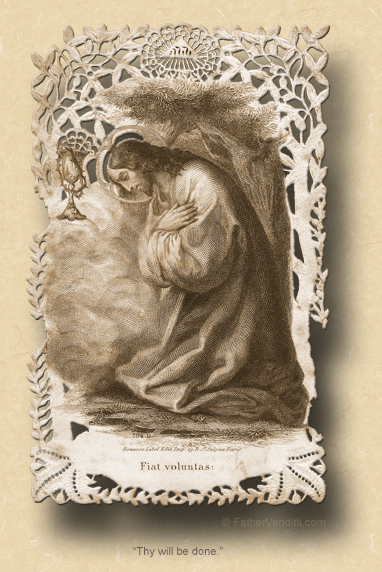

Every day we pray in the Lord’s Prayer, “Thy will be done,” and we mean it. But it’s always incumbent on us to remember that this presupposes that we’re open to God’s will, especially if most of our prayers are prayers of petition in which we are asking God for something. Let us never forget that God’s will is double-edged.

When I was first ordained and was teaching third grade religion, I used to tell the story of two little boys having a theological argument, one claiming that God often seems not to hear our prayers, and his companion being a little shocked at this and countering that, of course, God hears every prayer. So the first boy gives an example: he says, “You know that bicycle you wanted for your birthday?”

“Yes,” his companion replies.

“Did you pray for it?”

“Yes, I prayed for it every day.”

“Did you get it?”

“No.”

“There, you see? God didn’t answer your prayer.”

And, after thinking a bit, his companion replies, “Yes he did. He said, ‘No.’”

* In the extraordinary form, on ferias outside privileged seasons, the lessons come from the previous Sunday.

|